- Home

- Polinsky, Karen;

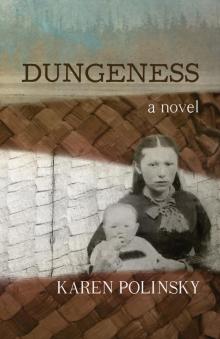

Dungeness

Dungeness Read online

Praise for Dungeness . . .

“Dungeness is a remarkable work. Karen Polinsky weaves a rich tapestry of fact and fiction, sprinkled with Northwest native art, language, and historical images, about the churning cultural changes of the Olympic Peninsula in the 1870s, seen through a young native girl’s experiences. But even more than this, Polinsky imbues her narrative with a deep and captivating sense of mystery.”

—Joe Upton, Alaska Blues: A Story of Freedom, Risk and Living Your Dream

“Polinsky’s innovative mix of fiction and fact is well designed to hold the interest of her intended readers—teenagers and young adults—while teaching them history essential to her tale. A mystery surrounding an actual 1868 massacre of Tsimshian Indians drives the suspenseful plot. Between chapters in which the fictional protagonist recounts her experiences, Polinsky presents short factual vignettes about events, circumstances, and Indian culture and beliefs. The information is admirably accurate, respectful of cultural differences, and relevant today as increasing numbers of people are again crossing cultural and racial lines to form families.”

—Dr. Alexandra Harmon, Indians in the Making: Ethnic Relations And Indian Identities Around Puget Sound (former chair of the AmericanIndian Studies Department at University of Washington)

DUNGENESS

By Karen Polinsky

© 2017 Karen Polinsky

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any means,

electronic or mechanical, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

paperback 978-1-945805-18-9

Illustrations

by

Cara Thompson

Cover Design

by

Brock Walker

Bink Books

a division of

Bedazzled Ink Publishing, LLC

Fairfield, California

http://www.bedazzledink.com

To Mary Ann Lambert and

her storytelling legacy,

and the three bands of S’Klallam:

Port Gamble, Jamestown & Elwa.

Acknowledgements

Dungeness, the novel with history, for me has been a journey across boundaries into new worlds. Along the way I have encountered so many exceptional people—with diverse talents and outlooks, from different places— united by their love for this Pacific Northwest landscape.

Here I would like to express my gratitude to a few of them:

To Marie Hebert, the Cultural Director of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, who gifted me with the collection of primary documents that began this search to rediscover the past.

To Dr. Alexandra Harmon, author of the seminal work Indians In the Making: Ethnic Relations and Indian Identities around Puget Sound. and former chair of the American Indian Studies Department at the University of Washington. Professor Harmon supported me in developing the first draft, setting a high standard, and deepening my understanding of the historic challenges of the regions.

To historians Michael Schein, author of The Bones Beneath Our Feet, and Katie Gale’s Llyn De Danaan, and Pam Clise, columnist for the Peninsula Daily News. To all of the scholars, writers and history buffs who volunteer at the Research Center of the Jefferson County Genealogical Society, especially Ann Candioto. What a resource!

To the earliest readers of the manuscript: To Zann and Craig Jacobrown, and Katie Zonoff, who love many of the same things I do. To my friends Kirrin Coleman, Sarah Hewes, Barbara Hume, Kelly Hume, Doug McKenzie and Peter Thomson. To my friend Eric Stahl, also an attorney, who advised me on copywright; still, any errors or oversights are entirely my own. To former Public Historian of the Museum of History and Industy Dr. Lorraine McConaghy, Bainbridge Arts and Humanities’ Kathleen Thorne, and Island novelist Carol Cassella for offering me advice on what to do next. To Jay Gusick and Bill Mawhinney for that final copy edit. Thank you.

For thinking outside of the box, to Michael D’Alessandro executive director of Northwind Arts Center and William Tennent, executive director of the Jefferson County Art and History Museum.

To Bennie Armstrong, the former chair of the Port Madison Suquamish Tribe, for offering his advice and support, and sharing his own stories. Without Bennie I wouldn’t have had the courage to finish the book or embark upon the collaborative exhibit. To Wendy Sampson, educational director of the Elwha S’Klallam Tribe, who strives to keep the language alive.

To the S’Klallam artists, who took a risk: to weaver Cathy MacGregor, a humorous, warm, versatile artist; to Jimmy Price, whose wit and wisdom I will never forget; and to Master-Carver Joe Ives who has enspirited my life with his undaunted optimism.

To all of the families, and the entire staff at the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. In particular, Tribal Chair Ron Allen, his assistant Ann Saergent, and publications director Betty Openheimer, for their help with the book and the exhibit. Also, thanks to the Olympic Peninsula Inter-Tribal Cultural Advisory Committee for their support and the Suquamish Tribal Council for their support.

To my children, Lee, Cynthia, and Adam Foley. To my husband Michael Foley, who believed in me. And to Cara Thompson, the designer of the book and the exhibit. Her insight, humor, and skill made this project possible. Best of all, she is a friend.

Last but not least, everlasting gratitude to Tom and Carol Taylor and Sherry Macgregor for sharing their time, and the precious past, with me.

About this Project

By Cara Thompson

Dungeness has been the uncovering a lost trail, a legendary Indian highway, more complex, haphazard, passionate, and enchanting than this book can convey. I say uncovering because we didn’t seem to have a map, or at least not one we could read. It seems we never accomplished what we set out to do, as we adventured. At times we embarked spontaneously, at times with unrealistic itineraries, wearing our bathing suits under our shorts, with bikes waving like a banner, barely strapped on to the back of her blue toy car questing to the Olympic Peninsula.

Before I came into this hurly-burly book bonanza, Karen had completed her own undertaking: researching and writing Dungeness for more than 10 years, calling on some magical inspiration from the curiosity, candor, and pride of one S’Klallam woman, an original. When Karen finished, the book had become more than just a work of historical fiction, but a coming-of-age story with some history, some philosophy, some native lore, some regional myth, and some-thing that had never been done before! Karen knew that sharing her story would call for more than just words, but a whole crew of imaginative people coming together to shape an old story in a new way.

At this time Karen asked me to add artwork to the story and design the text. As we struggled, now together, to assemble the pages, we fell upon the secret message of the hidden narrative, while listening to the stories of the visionary artists Joe Ives, Jimmy Price, and Cathy MacGregor; eating Indian tacos at a pow-wow at the Port Gamble Tribe; dividing an apple pancake with Mary Ann Lambert’s family; and visiting S’Klallam language classes. We spent the summer of 2015 finishing the book while learning how to carve our very own portrait masks from a wise Master Carver! As we ventured further into the unknown, whether our mini-expeditions were successful or not, at the end of the day there was always a cider and a salmon sandwich at Sirens, a distinguished pub in historic Port Townsend.

The secret message: if you want to shine a light on something: look, look back, look inside, look around, and listen. What we learned on the journey has inspired the táʔkʷt (to shine a light on something) revisionist-history contemporary art exhibition.

However creative, unsystematic, or outlandish our project became, Dungeness kept moving forward, inspiring a collaborative, multimedia art exhibit at Northwind Arts Center in Po

rt Townsend, a symposium led by three of the foremost women authors writing on S’Klallam history, and a series of gratitude gatherings for all those who made this project possible.

In Karen’s words: “This entire project has been forged in friendship,” with the Tribes, the families, the galleries, the librarians, the historians, the artists, the past, the present, and between Karen and me. Friendship has no map; friends make maps together. Dungeness is just a sappy glistening of what we uncovered. The book is our map to a place of love and chance.

Prologue

September 1900

Dear Reader—

The night is still. The waning moon illumines the white-and-black lighthouse, surmounted by a red lantern room. The universe whispers, “t-sh.”

Below, on the south side of the Dungeness sandspit, a beached fleet of canoes: forty-to-fifty feet in length, honed with an axe blade to withstand a sea journey of five hundred miles or more. It’s a rich fleet, pregnant with sacks of flour, sugar, and soap. In addition: three tea kettles, two sets of brass hinges, eighty used blankets; all purchased with dollars earned from the harvesting of hops in the dry heat of summer.

On top of the dune, a half-dozen canvas tents billow as if breathing. Inside, eighteen Tsimshians, hotly at rest. The men place their tough bellies on top of the sturdy hips of their wives. A small boy clasps his fingers to make a pillow for his cheek; a little girl sighs, pressing her palms in between her knees. Together they dream of the welcome they will receive in their home village on the north Pacific shore, greeted by sentry poles with round eyes and grimacing grins, fifty-to-eighty feet high.

Outside, two dozen makeshift warriors wait for a black wind to rise. The leader of the ambush—the S’Klallam call him Nu-Mah the Bad—lifts up his hand, hatchet-like. To whites he’s known as Lame Jack. By any name, he’s a scoundrel. Lame Jack lets the axe blade drop.

At the signal, the S’Klallam bury their weapons, splitting the flesh and cracking the cartilage and bones of the seething canvas beast. The blood of bodies far from home unfurls on top of the pebbly beach like a map. A raft of seals, their heads bobbing on top of the waves, turn their eyes into fire. It is their role to witness what happens here. From the fall to the winter, they will groan about it and roar.

On September 21, 1868, eighteen Northern Indians were transformed into seventeen corpses. Nusee-chus, a Tsimshian girl too frightened to cry, sacrificed a pair of silver pendant earrings, her life, and that of her unborn son. The eighteenth murdered body?

In this journal I will clarify how the earrings, created by a Tsimshian craftsman for his new bride, came to me. For a while the earrings belonged to my mother Annie, also a girl bride, though a reluctant one. She was never seen without them. As a baby, I can still recall reaching out to still their eerie brightness. When I was six, my reluctant mother—vexed by fear and love—branded me with the silver fish. This violent sacrificial act, the call to action of my quest, a mystic journey to unknown places across the great divide between life and death.

In these pages, I explore the events of my coming of age in the Pacific Northwest, more or less in the sequence in which they occurred. In alternating chapters, I have composed short essays about local history, in chronologic order, to brighten my passage.

Today, I am twenty, a teacher of Native American children in Kansas. More educated. Not as clumsy. Wiser, perhaps. Intuitive by nature but not as keen as some. If you question my perception or doubt any +of the claims put forth here, ask Annie.

I still have a lot to learn; not from the dead leaves of books, but from the living landscape, seeding the songs of our ancestors, who, like fossil ferns, have buried their knowledge deep within the earth. Newcomers who disembark here trespass upon their bones. The subterranean whispers of those who belong to this place—without whom this landscape cannot exist—shadow our past and light the way to our future. The story of the S’Klallam people is our story. The fate of the indigenous is our fate.

Choosing where to begin is like dropping an anchor from a random star. According to S’Klallam belief, there is no true beginning, and no end: death, merely a crossing over to a wider, deeper, brighter awareness. Still, to strip the moss off the mystery, one must start somewhere. I begin where consciousness begins: As a wide-eyed infant on the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the autumn of 1876.

I am that star.

This is my story.

It is random.

It is everyone’s.

When our young men grow angry at some real or imaginary wrong, and disfigure their faces with black paint, their hearts, also, are disfigured and turn black, and then their cruelty is relentless and knows no bounds, and our old men are not able to restrain them.

—Chief Seattle, from a speech published in The Seattle Sunday Star, 1854

There is no circle any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.

—Nicolas Black Elk, the final line of his dream-vision, 1932

Invariably there are three sides to any story, whether verbal or written. Herein, then, is contained a chain of stories based on facts, and having three sides: The White man’s side, the Indian’s side and Public Opinion’s side.

—Mary Ann Lambert, from Dungeness Massacre and Other Regional Tales, 1961

Part I

On The Strait

Of Juan de Fuca

1

The Aia’nl

(From Klallam Ethnography

by Erna Gunther)

There is a tidal pool at the end of the spit where the ducks often gather. He saw a woman walk. It was strange . . .

. . . when he reached home he could not eat his evening meal . . .

She stood on the opposite side of the fire and looked at him.

He called to his uncle to drive her away.

“Don’t you see her?”

For many nights she came in this same way.

His people begged him not to be afraid. They told him she would give him the power to see far off and find missing things.

Still, he did not want her, for her appearance was so terrible. She was very dark with a purple forehead and large round eyes, without corners like ours. Her eyelashes were white.

At last she came no more.

2

The Sick Fox

(c. 1876)

At high tide the five-mile spit of sand is like a bent elbow. At the tip of the crooked finger, the New Dungeness Light Station overlooks the sandbar with a shifting, uneasy regard.

A girl, restless, props her chin up on the rail of their fragrant plank house. A lock lashes at her squinched forehead. She loops it around her boney ear, a convenient oarlock. Pendant earrings shaped like fish banter in the sunlight.

She shrugs once, and then reaches for the cradleboard leaning on the sill. Beside it, a wide-weave pot-bellied oyster basket. In her arms, an infant sausaged inside a rolled cedar mat. She secures the bundle to the cedar plank. A leather strap across her forehead supports the basket, which rocks against her hip. Thus encumbered, Annie races down the oozing path in between the mucus grass to the water’s edge.

Her flat right palm shields her eyes.

It’s a clean morning full of sun, one made for sport.

On the horizon his bright green troller with its matchstick mast, bobbing. The old man, Charles Langlie, Norwegian sailor turned farmer-fisherman, anchored out a short distance from the Dungeness sandbar. He can’t expect to bring in much, not without help. According to Carl, Jake-the-Makah ought to be here on the other end of a purse seine net. However, when Jake shows up tomorrow, Carl knows better than to question him or display his irritation. Carl may be the boss, but Jake is prideful and won’t put up with much.

With or without his hired man, the next step is to deliver one or two basins of the smaller fish to the cannery at S’Klallam Bay. Annie figures, even with a modest take, he won’t be back for hours.

How did Eliza-the-third, E’ow-itsa in Coast Salish, aka Seya, persuade the fourteen-year-old S’Klallam princess to wed t

he old Norwegian mariner?

What makes her stay?

At first, she reasoned, or at least hoped, a liaison with a white husband almost four times her age could only increase her status. Instead, she has become his near slave. Each day Annie fetches potable water from the creek, prepares fish stew, boils water to scrub his cuffs and collars, and gathers kindling from the beach. All this, before the baby!

The fisherman, with a halo of white hair and a glowering aspect, can claim one or two finer points, as well as some unanticipated talents. With no cash to pay the canoe-preacher, he managed to throw up a decent house. In the evening, Carl sits by the fire uncoiling his sleeves. On the little iron cook stove he crisps glowing ginger cookies with a spicy aftertaste. Despite his rough manners, he’s never rough with her.

The story of how he netted his unsought treasure, he embellishes. In nearby Sequim–not exactly a town but instead a few signposts buried in the mud–cannery workers, lumbermen, farmers, and oystermen meet at a tavern, The Corners. Here, Carl toasts the passage of time with Hjalmar Henning, an original pioneer who makes his living hauling logs with an ox team.

At the bar, Henning coughs up the coins, which gives him the right to bellyache: about farmers who pay in kind instead of cash; claim jumpers quicker than his scatter shot; but worst of all, where are all the women? Can’t find a girl—white, brown, red, or Chinese—to brand a steak, wring his socks, or measure out his whisky.

To prick him on, Carl relates a marvelous confabulation, about how a damned alcoholic snagged a princess. Carl should know by now that the term “princess,” and other nomenclature of European aristocracy, increasingly offend the local Natives. These satiric honorifics mock historic S’Klallam hierarchies, a source of great pride. He’s aware, but he can’t help it: to Carl, Annie is, and always will be, his princess.

Dungeness

Dungeness